News Letter 5853-044

The 1st Year of the 4th Sabbatical Cycle

The 22nd year of the Jubilee Cycle

The 16th day of the 11th month 5853 years after the creation of Adam

The 11th Month in the First year of the Fourth Sabbatical Cycle

The 4th Sabbatical Cycle after the 119th Jubilee Cycle

The Sabbatical Cycle of Sword, Famines, and Pestilence

February 3, 2018

Shabbat Shalom To the Royal Family,

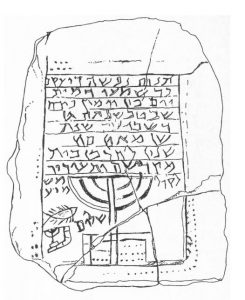

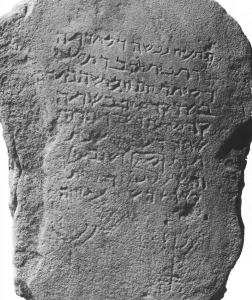

The Picture above is of the two Tombstones in the Shrine of the Book Museum in Jerusalem. And I was so happy to see them in person.

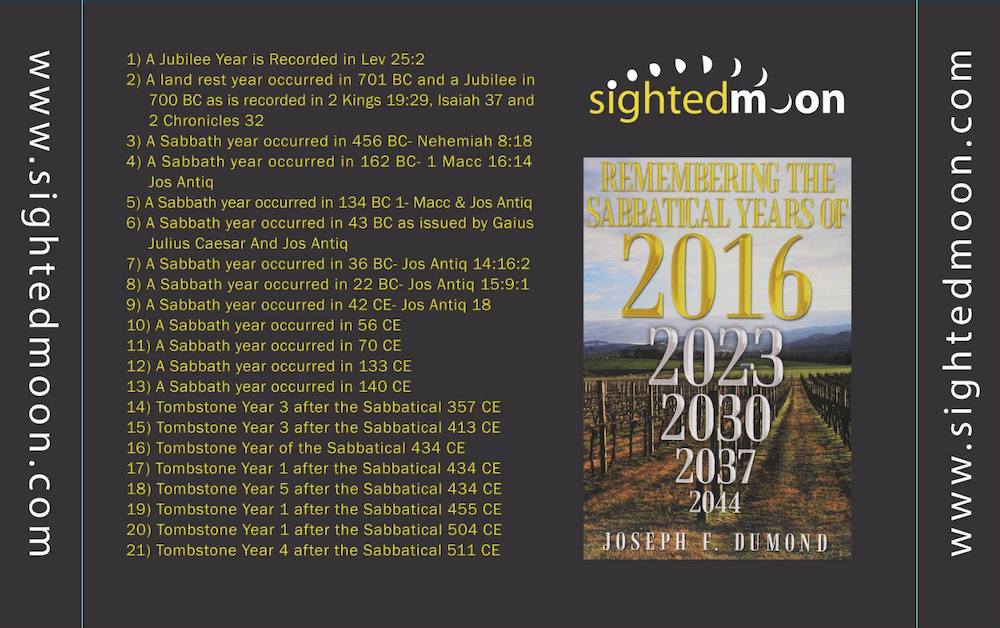

The chart below has been the one we have been posting for a few year to show the Sabbatical and Jubilee years we had discovered. But it is now out of date.

-

- A Jubilee Year is Recorded in Lev 25:2

- A land rest year occurred in 701BC and a Jubilee in 700BC as is recorded in 2 Kings 19:29, Isaiah 37 & Chronicles 32

- A Sabbath year occurred in 456 BC – Nehemiah 8:18

- A Sabbath year occurred in 162 BC – 1 Macc 16:14 Jos Antiq.

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 134 BC 1 – Macc & Jos Antiq.

- A Sabbath year occurred in 43 BC as Issued by Gaius Julius Cesar and Jos Antiq.

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 36 BC – Jos Antiq. 14:16:2

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 22 BC – Jos Antiq. 15:9:1

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 42 CE – Jos Antiq. 18

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 56 CE –

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 70 CE –

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 133 CE –

- A Sabbath Year occurred in 140 CE –

- Tombstone Year 3 after the Sabbatical 357 CE –

- Tombstone Year 3 after the Sabbatical 413 CE –

- Tombstone Year of the Sabbatical 434 CE –

- Tombstone Year 1 after the Sabbatical 434 CE –

- Tombstone Year 5 after the Sabbatical 434 CE –

- Tombstone Year 1 after the Sabbatical 455 CE –

- Tombstone Year 1 after the Sabbatical 504 CE –

- Tombstone Year 4 after the Sabbatical 511 CE –

Even our Banner that we have been dragging around the world and putting up in Africa, Philippines, Israel and North America is also out of date. But the information found in our book Remembering the Sabbatical year of 2016 remains accurate and still true. We cannot urge you strongly enough to get a copy of this book and read it and then share it. And when you do get it order the companion to it, The 2300 Days of Hell.

It is only by understanding the Sabbatical and Jubilee cycles that you can understand end time prophecy. It is the only way. So do get both the books today and begin to learn this most amazing part of your bible.

You are about to see all the evidence I have for all 34 Sabbatical and Jubilee years that I have now been able to collect. For the first time, this will all be in one place here on our website and in this article.

But we have not put all the research here. We have left you links to the research for each year identified. But there is much more work to be done. I have knowledge of 30 more tombstones from Zoar. I have just learned there are another 300 Tombstones that might have inscriptions dating them to the Sabbatical years.

I believe there are more Tombstones in Crimea that would also use the Sabbatical year and the destruction from the Temple to date the death of those represented by each stone and I have also strong suspicions that there are more to be found in the Jewish cemeteries around Rome as well.

Tombstones written in the Aramaic and Hebrew inscriptions dating from the Destruction of the Temple are very rare to find and we have 12 of them discovered to date. Like I said, I have read there are about 30 known.

Each and every one of you can help us find more. You will see that I am missing pictures of Tombstones. You can help find them. You can find others and document them so we can add them to this list.

I have sent the list I have with more tombstones on it to be translated by a friend. It should be done in a months time and then I will update this list again.

Now to all those naysayers; to all those who have their pet theories. You not only have to prove al the facts of the chronology I have shared in our book Remembering the Sabbatical year of 2016, to be wrong but you must also prove each and every one of these 34 proofs that we are again presenting to you, you must prove each of them to be false as well.

Since I first learned of these things in the winter of 2004/5 I have had many who disagreed and many you would not check it out, but I have not one person come and prove it wrong. But the frustrating thing I have to had to deal with is the many Torah teachers who have buried their heads in the sand and refused to examine the facts and learn when the Sabbatical year is. It is just as Holy as the Moedim and weekly Sabbaths. Yet too many dismiss it as nothing of interest.

How many will be told I never knew you and how many will be welcomed into the Kingdom of that Millennial rest which the Sabbatical and Jubilee years show you when it is to begin?

May Yehovah bless you to understand these things and to be able to share them with others so that they too can begin to learn.

# 1 Jubilee Year 1337 BC

# 1 1337 BC – A Jubilee year is Recorded in

Lev 25:2 “Speak to the people of Israel and say to them, When you come into the land that I give you, the land shall keep a Sabbath to the Lord. For six years you shall sow your field, and for six years you shall prune your vineyard and gather in its fruits, but in the seventh year, there shall be a Sabbath of solemn rest for the land, a Sabbath to the Lord.

The year Joshua entered the Promised land was 1337 BC or 2500 years after the Creation of Adam. It was one of only two Jubilee years mentioned in the entire Bible

“# 2 Sabbatical Year 869 BC”

869 BC. A Sabbatical year. Jehoshaphat ascended the throne at the age of thirty-five and reigned for twenty-five years. He spent the first years of his reign fortifying his kingdom against the Kingdom of Israel. His zeal in suppressing the idolatrous worship of the “high places” is commended in 2 Chronicles 17:6. In the third year of his reign, Jehoshaphat sent out priests and Levites over the land to instruct the people in the Law, an activity that was commanded for a Sabbatical year in Deuteronomy 31:10–13. The author of the Books of Chronicles generally praises his reign, stating that the kingdom enjoyed a great measure of peace and prosperity, the blessing of God resting on the people “in their basket and their store.”

R. Thiele held that he became coregent with his father Asa in Asa’s 39th year, 872/871 BC, the year Asa was infected with a severe disease in his feet, and then became sole regent when Asa died of the disease in 870/869 BC, his own death occurring in 848/847 BC. So, Jehoshaphat’s dates are taken as one year earlier: co-regency beginning in 873/871, sole reign commencing in 871/870, and death in 849/848 BC.

2 Ch 17:8-11 In the third year of his reign he sent his officials, Ben-hail, Obadiah, Zechariah, Nethanel, and Micaiah, to teach in the cities of Judah; and with them the Levites, Shemaiah, Nethaniah, Zebadiah, Asahel, Shemiramoth, Jehonathan, Adonijah, Tobijah, and Tobadonijah; and with these Levites, the priests Elishama and Jehoram. And they taught in Judah, having the Book of the Law of the Lord with them. They went about through all the cities of Judah and taught among the people.

“# 3 Sabbatical Year 701 BC”

A Sabbatical year is recorded in 701 BC in 2 King 19:29, Isaiah 37, and 2 Chronicles 32 Sennacherib attacks Hezekiah

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj03Chap.pdf

2 Kings 19:29 “And this shall be the sign for you: this year eat what grows of itself, and in the second year what springs of the same. Then in the third year sow and reap and plant vineyards, and eat their fruit.

“# 4 Jubilee Year 700 BC”

A Jubilee year in 700 BC as recorded in 2 King 19:29, Isaiah 37, and 2 Chronicles 32

This is the 2nd of only two Jubilee years mentioned in the entire Bible, and when you count by 49 from one to the other they match. The first one was in the year 2500 after the creation of Adam and was the first year of the 52nd Jubilee cycle. 700 B.C. was the 3137th year after the creation of Adam and the first year of 65th Jubilee cycle.

2 Kings 19:29 “And this shall be the sign for you: this year eat what grows of itself, and in the second year what springs of the same. Then in the third year sow and reap and plant vineyards, and eat their fruit.

“# 5 Sabbatical Year 456 BC”

A Sabbatical Year is recorded in 456 BC – Nehemiah 7:73-8:18

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj11Chap.pdf

So the priests, the Levites, the gatekeepers, the singers, some of the people, the temple servants, and all Israel, lived in their towns.

And when the seventh month had come, the people of Israel were in their towns.

And all the people gathered as one man into the square before the Water Gate. And they told Ezra the scribe to bring the Book of the Law of Moses that the Lord had commanded Israel. So Ezra the priest brought the Law before the assembly, both men and women and all who could understand what they heard, on the first day of the seventh month. And he read from it facing the square before the Water Gate from early morning until midday, in the presence of the men and the women and those who could understand. And the ears of all the people were attentive to the Book of the Law. And Ezra the scribe stood on a wooden platform that they had made for the purpose. And beside him stood Mattithiah, Shema, Anaiah, Uriah, Hilkiah, and Maaseiah on his right hand, and Pedaiah, Mishael, Malchijah, Hashum, Hashbaddanah, Zechariah, and Meshullam on his left hand. And Ezra opened the book in the sight of all the people, for he was above all the people, and as he opened it all the people stood. And Ezra blessed the Lord, the great God, and all the people answered, “Amen, Amen,” lifting up their hands. And they bowed their heads and worshiped the Lord with their faces to the ground. Also Jeshua, Bani, Sherebiah, Jamin, Akkub, Shabbethai, Hodiah, Maaseiah, Kelita, Azariah, Jozabad, Hanan, Pelaiah, the Levites, helped the people to understand the Law, while the people remained in their places. They read from the book, from the Law of God, clearly, and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.

And Nehemiah, who was the governor, and Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites who taught the people said to all the people, “This day is holy to the Lord your God; do not mourn or weep.” For all the people wept as they heard the words of the Law. Then he said to them, “Go your way. Eat the fat and drink sweet wine and send portions to anyone who has nothing ready, for this day is holy to our Lord. And do not be grieved, for the joy of the Lord is your strength.” So the Levites calmed all the people, saying, “Be quiet, for this day is holy; do not be grieved.” And all the people went their way to eat and drink and to send portions and to make great rejoicing, because they had understood the words that were declared to them.

Feast of Booths Celebrated

On the second day the heads of fathers’ houses of all the people, with the priests and the Levites, came together to Ezra the scribe in order to study the words of the Law. And they found it written in the Law that the Lord had commanded by Moses that the people of Israel should dwell in booths during the feast of the seventh month, and that they should proclaim it and publish it in all their towns and in Jerusalem, “Go out to the hills and bring branches of olive, wild olive, myrtle, palm, and other leafy trees to make booths, as it is written.” So the people went out and brought them and made booths for themselves, each on his roof, and in their courts and in the courts of the house of God, and in the square at the Water Gate and in the square at the Gate of Ephraim. And all the assembly of those who had returned from the captivity made booths and lived in the booths, for from the days of Jeshua the son of Nun to that day the people of Israel had not done so. And there was very great rejoicing. And day by day, from the first day to the last day, he read from the Book of the Law of God. They kept the feast seven days, and on the eighth day there was a solemn assembly, according to the rule.

“# 6 Sabbatical Year 330 BC”

A Sabbatical Year recorded in 330 BC – The Remission of taxes under Alexander the Great for Sabbatical years. Josephus records an account of Alexander the Great exempting the Jews from having to pay taxes during sabbatical years (Antiquities, bk. 11, ch. 8, sect. 4-5).

- But Sanballat thought he had now gotten a proper opportunity to make his attempt, so he renounced Darius, and taking with him seven thousand of his own subjects, he came to Alexander; and finding him beginning the siege of Tyre, he said to him, that he delivered up to him these men, who came out of places under his dominion, and did gladly accept of him for his lord instead of Darius. So when Alexander had received him kindly, Sanballat thereupon took courage, and spake to him about his present affair. He told him that he had a son-in-law, Manasseh, who was brother to the high priest Jaddua; and that there were many others of his own nation, now with him, that were desirous to have a temple in the places subject to him; that it would be for the king’s advantage to have the strength of the Jews divided into two parts, lest when the nation is of one mind, and united, upon any attempt for innovation, it prove troublesome to kings, as it had formerly proved to the kings of Assyria. Whereupon Alexander gave Sanballat leave so to do, who used the utmost diligence, and built the temple, and made Manasseh the priest, and deemed it a great reward that his daughter’s children should have that dignity; but when the seven months of the siege of Tyre were over, and the two months of the siege of Gaza, Sanballat died. Now Alexander, when he had taken Gaza, made haste to go up to Jerusalem; and Jaddua the high priest, when he heard that, was in an agony, and under terror, as not knowing how he should meet the Macedonians, since the king was displeased at his foregoing disobedience. He therefore ordained that the people should make supplications, and should join with him in offering sacrifice to God, whom he besought to protect that nation, and to deliver them from the perils that were coming upon them; whereupon God warned him in a dream, which came upon him after he had offered sacrifice, that he should take courage, and adorn the city, and open the gates; that the rest should appear in white garments, but that he and the priests should meet the king in the habits proper to their order, without the dread of any ill consequences, which the providence of God would prevent. Upon which, when he rose from his sleep, he greatly rejoiced, and declared to all the warning he had received from God. According to which dream he acted entirely, and so waited for the coming of the king.

- And when he understood that he was not far from the city, he went out in procession, with the priests and the multitude of the citizens. The procession was venerable, and the manner of it different from that of other nations. It reached to a place called Sapha, which name, translated into Greek, signifies a prospect, for you have thence a prospect both of Jerusalem and of the temple. And when the Phoenicians and the Chaldeans that followed him thought they should have liberty to plunder the city, and torment the high priest to death, which the king’s displeasure fairly promised them, the very reverse of it happened; for Alexander, when he saw the multitude at a distance, in white garments, while the priests stood clothed with fine linen, and the high priest in purple and scarlet clothing, with his mitre on his head, having the golden plate whereon the name of God was engraved, he approached by himself, and adored that name, and first saluted the high priest. The Jews also did all together, with one voice, salute Alexander, and encompass him about; whereupon the kings of Syria and the rest were surprised at what Alexander had done, and supposed him disordered in his mind. However, Parmenio alone went up to him, and asked him how it came to pass that, when all others adored him, he should adore the high priest of the Jews? To whom he replied, “I did not adore him, but that God who hath honored him with his high priesthood; for I saw this very person in a dream, in this very habit, when I was at Dios in Macedonia, who, when I was considering with myself how I might obtain the dominion of Asia, exhorted me to make no delay, but boldly to pass over the sea thither, for that he would conduct my army, and would give me the dominion over the Persians; whence it is that, having seen no other in that habit, and now seeing this person in it, and remembering that vision, and the exhortation which I had in my dream, I believe that I bring this army under the Divine conduct, and shall therewith conquer Darius, and destroy the power of the Persians, and that all things will succeed according to what is in my own mind.” And when he had said this to Parmenio, and had given the high priest his right hand, the priests ran along by him, and he came into the city. And when he went up into the temple, he offered sacrifice to God, according to the high priest’s direction, and magnificently treated both the high priest and the priests. And when the Book of Daniel was showed him wherein Daniel declared that one of the Greeks should destroy the empire of the Persians, he supposed that himself was the person intended. And as he was then glad, he dismissed the multitude for the present; but the next day he called them to him, and bid them ask what favors they pleased of him; whereupon the high priest desired that they might enjoy the laws of their forefathers, and might pay no tribute on the seventh year. He granted all they desired. And when they entreared him that he would permit the Jews in Babylon and Media to enjoy their own laws also, he willingly promised to do hereafter what they desired. And when he said to the multitude, that if any of them would enlist themselves in his army, on this condition, that they should continue under the laws of their forefathers, and live according to them, he was willing to take them with him, many were ready to accompany him in his wars.

“# 7 Sabbatical Year 162 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 162 B.C. Antiochus Eupator’s siege of the fortress Beth-zur (Ant. 12.9.5/378, 1 Maccabees 6:53)

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj12Chap.pdf

Yet at the last, their vessels being without victuals—??? ? £???µ?? Á??? ? <??? (BY REASON OF IT BEING THE SEVENTH YEAR), and they in Judaea, that were delivered from the nations, had eaten up the residue of the store. There were but a few left in the sanctuary, because famine did so prevail against them, that they fain to disperse themselves, every man to his own place. (1 Macc., (BY REASON OF IT BEING THE SEVENTH YEAR), and they in Judaea, that were delivered from the nations, had eaten up the residue of the store. There were but a few left in the sanctuary, because famine did so prevail against them, that they fain to disperse themselves, every man to his own place. (1 Macc., 6:53f)

Their supply of food, however, had begun to give out, for the ?????? (stored produce) had been consumed, and THE GROUND HAD NOT BEEN TILLED THAT YEAR, BUT HAD REMAINED UNSOWN ú??? ??? ? ?<??? ? £???µ?? Á??? (BECAUSE IT WAS THE SEVENTH YEAR), DURING WHICH OUR LAW OBLIGES US TO LET IT LIE UNCULTIVATED. Many of the besieged, therefore, ran away because of the lack of necessities, so that only a few were left in the Temple. (Jos., Antiq., 12:9:5) (BECAUSE IT WAS THE SEVENTH YEAR), DURING WHICH OUR LAW OBLIGES US TO LET IT LIE UNCULTIVATED. Many of the besieged, therefore, ran away because of the lack of necessities, so that only a few were left in the Temple. (Jos., Antiq., 12:9:5)

“# 8 Sabbatical Year 134 BC”

A Sabbatical Year in 134 B.C. John Hyrcanus’s siege of Ptolemy in the fortress of Dagon, which is described both in Josephus ( 13.8.1/235; War of the Jews 1.2.4/59-60) and 1 Maccabees (16:14-16)

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj14Chap.pdf

But while the siege was being protracted in this manner, there came around the year in which the Jews are wont to remain inactive, for they observe this custom every seventh year, just as on the seventh day. And Ptolemy, being relieved from the war for this reason, killed the brothers and mother of Hyrcanus, and after doing so, fled to Zenon, surnamed Cotylas, who was tyrant of the city of Philadelphia. (Jos., Antiq., 13:8:1)

The siege consequently dragged on until the year of ú??? (not working the ground)7 came round, which is kept septennially by the Jews as a period of inaction, like the seventh day of the week. Ptolemy, now relieved of the siege, put John’s brethren and their mother to death and fled to Zenon, surnamed Cotylas, the tyrant of Philadelphia. (Jos., Wars, 1:2:4)

7 The term ú??? (argon) means, “not working the ground, living without labour,” see GEL, p. 114.

“# 9 Sabbatical Year 78 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 78 B.C. The 25th year of King Alexander Jannaaeus and the minting of Shmita Coins

King Alexander Jannaeus 103-76 BC

Coins 78 B.C. “King Alexander, Year 25” (in Greek) and “Yehohanan, the king, Year 25” (in Hebrew)

Unlike his predecessors who asserted themselves on coins to be “High Priest” and ethnarchs, Alexander Jannaeus proclaimed himself to be both High Priest and King. The title “King” was not allowed for Judean rulers since the days Zerubbabel. Yet on coins issued early in his reign, he laid claim to both titles. After the Pharisees took serious issue with the arrogance of this Hasmonean ruler, he overstruck most of those coins, and, at the same time, minted additional coins, with the more modest titles, like his predecessors: “High Priest and (head of) the council of the Jews” (i.e., ethnarch).

This act did not satisfy the Pharisees. After six years of civil war (93–87 BCE) between Alexander Jannaeus with the Sadducees against the Pharisees, he finally and severely asserted his position as King. The Pharisees had invited the Greeks to come to take Jerusalem. For this act of “treason,” Alexander Jannaeus crucified 800 Pharisees in Jerusalem’s city centre. His self-proclamation of kingship was again signified by minting coins with the title “King Alexander” in Greek and “Yehonatan, the king” in Hebrew. Also, the symbol of the star encircled by a royal diadem (see below, right) provides two emblems of the priestly and royal Messiahs (cf. Balaam’s prophecy of the Scepter and the Star, popular symbols of the coming Messiahs during the first and second centuries BCE).

78 BCE: On the twenty-fifth anniversary of his rule, he minted dated coins on the Sabbatical Year. Year 25 prutot and leptas known as “widow’s mites”, by far the most abundant Jewish coin in antiquity, were minted during a sabbatical year: 78 BCE. In this case, the star and the diadem are on opposite sides of the coin.

After reviewing the cycle of dated coins, it became apparent that numerous bronze issues of coins that were produced by Jewish leaders happened to coincide with Sabbatical years. These tended to be small bronze coins, prutot and lepta (half prutot) and were produced in unusually large numbers. The emblems upon the coins tend to be connected with grains and fruits which were scarce or lacking during those years, due to prohibitions on harvesting grains and fruit during those years due to prohibitions on harvesting. Even for similar denominations of coins that did not bear dates, it became apparent that during the early years from the years of John Hyrcanus I until the early part of the reign of Archelaus the double cornucopia was used almost exclusively for the smaller bronze issues. From the last years of Archelaus’ reign onward various grains and fruits connected with the various feasts, especially the feast of booths, were used. These coins may also have been produced in particular during sabbatical years.

Why were these coins prevalent during Sabbatical Years? One must first consider the nature of the economy during these years. Since the normal means of barter by kind, produce, was hampered, coinage became the primary means of commerce during these difficult years. Here, the ethnarch/king apparently flooded the economy with small denomination bronze coins in order to bolster the economy and alleviate the financial crisis brought on by shortages of produce during the Shmitta when bartering in kind proved difficult. To a certain extent the king was improving his image as a redeemer before his people by paying a debt to society during a year of severe hardships and potential financial reversals.

During the revolts, when messianic expectation was a key rallying point, the coins used the more unusual term (hlag instead of hfimu) for the sabbatical year which was used to bolster the messianic expectation of the period. The Messiah as the GOEL/Redeemer would arrive during as Sabbatical year or in a Jubilee year to redeem his people from debt, slavery and oppression and to atone for their sins before God. During other, non-sabbatical, years the term “freedom of Zion/Jerusalem” was used instead. During the first year of the second revolt, (133) a sabbatical year, the term hlag was not limited to the bronze denominations but was added to silver coins as well.

There is evidence from dated coins that this practice of flooding the economy with small bronzes during the sabbatical years took place especially during the reigns of “kings” such as Alexander Jannaeus, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and during both Jewish Revolts (only “Geulat” issues) against Rome. This suggests that the case may be the same for many non–dated issues as well. The following list enumerates some of these coins whose dates (or dates with significant inscriptions) coincide with sabbatical years:

- 78 BCE: year 25 of Alexander Jannaeus

- 36 BCE: year 3 of Herod the Great

- 43 CE: year 6 of Agrippa I

- 70 CE: year 4 of the First Revolt, “geulat Tsion”

- 133 CE: year 1 of the Second Revolt, “geulat Yisrael”

From:

S. Pfann, ‘Dated Bronze Coinage of the Sabbatical years of Release and the First Jewish City Coin’. Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 24 (2006) 101-113.

“# 10 Sabbatical Year 43 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 43 B.C. A decree issued by Gaius Julius Caesar and published by Josephus in his work entitled, The Antiquities of the Jews 14:10:5

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj15Chap.pdf

Gaius Caesar, Imperator for the second time, has ruled that they (the Jews) shall pay a tax for the city of Jerusalem, Joppa excluded, every year except in the seventh year, which they call the ????????? (sabbatikon; sabbath) year, because in this time they neither take fruit from the trees nor do they sow. And that in the second year they shall pay the tribute at Sidon, consisting of one fourth of the produce sown, and in addition, they shall also pay tithes to Hyrcanus and his sons, just as they paid to their forefathers. . . . It is also our pleasure that the city of Joppa, which the Jews had held from ancient times when they made a treaty of friendship with the Romans, shall belong to them as at first; and for this city Hyrcanus, son of Alexander, and his sons shall pay tribute, collected from those who inhabit the territory, as a tax on the land, the harbour and exports, payable at Sidon in the amount of 20,675 modii every year EXCEPT IN THE SEVENTH YEAR, WHICH THEY CALL THE SABBATH YEAR, wherein they neither plough nor take fruit from the trees. (Jos., Antiq., 14:10:6)

“# 11 Sabbatical Year 36 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 36 B.C.

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj16Chap.pdf

Herod the Great’s siege of Jerusalem, as described by Josephus Antiquities 14:16:2 And acting in desperation rather than with foresight, they (the people of Jerusalem) persevered in the war to the very end—this in spite of the fact that a great army surrounded them and that they were distressed by famine and the lack of necessities, for a °???µ????? (hebdomatikon, i.e. seventh) year happened to fall at that time. (Jos., Antiq., 14:16:2)

King Herod The Great Schmita Coins 36 B.C.

Herod the Great was appointed King over Judea by Augustus in 40 BCE. However, it was not until 36 BCE that he managed to take Jerusalem by siege and to oust Antigonus from his throne. According to Josephus, the siege was during a Sabbatical year, utilizing the cities foodstuffs for his troops, which added to the plight of the people of that city. His bronze coinage no doubt signified his victory but also would have been intended to alleviate the financial crisis that prevailed in the city. The Year 3 Sabbatical Year coin set which covered nearly every denomination, 8 prutot, 4 prutot, 2 prutot, 1prutah. No dated version of the smallest denomination, the lepton, was produced (perhaps due to the paucity of surface area on this coin for a date). However, one candidate for a non-dated version could be the eagle lepton(Hendin 501) which reflects a similar boldness in the use of non-Jewish iconography as the dated denominations, and a single cornucopia linked to the coins of his predecessors the Hasmoneans.

Herod the Great may have minted coins throughout his reign. However the major occasions to mint coins included commemoration of major events, including the completion of the harbor of Caesarea (Hendin p. 168 no. 502). However the apparent abundance of coins whose dates coincide with sabbatical years would imply that sabbatical years were key occasions to produce coins, for reasons already mentioned.

As in the case of the Year 3 Sabbatical Year coin set which covered nearly every denomintation, 8 prutot, 4 prutot, 2 prutot, 1 prutah, it appears that another set, the tripod series, may have been produced for Year ten, each with and “X” or “+” prominently displayed in the center of the verso within a royal diadem (suggested by Donald Ariel). This series included only the smaller denominations, 2 prutot, 1 prutah, 1 lepton. The motifs that unifies this set is the diadem and the tripod. (A lesser number of the leptons of this tripod series were minted, without the diadem, but with a palm branch.)

“# 12 Sabbatical Year 29 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 29 B.C. Herod the Great Shmita Coinage.

The Sabbatical Year 29 followed on the heels of a number of disastrous set-backs during the preceding years, each, in itself could lead to a difficult Sabbatical year. These were: 1) Anthony and Cleopatra were defeated at the Battle of Actium; 2) Herod was defeated by the Nabateans; and most importantly, 3) a devastating earthquake destroyed much of Judea and took the lives of thousands of its inhabitants.

“# 13 Sabbatical Year 22 BC”

A Sabbatical year in 22 B.C. Josephus Antiquities 15:9:1

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj21Chap.pdf

Since we are now in Herod’s fifteenth year, it is all important for our study to notice that during this harvest period Herod sent “into the country (of Judaea) no fewer than 50,000 men” to help in the harvest, and that this assistance “helped his damaged realm recover.” In short, Herod’s fifteenth year, like his thirteenth and fourteenth, could not be a sabbath year because the Jews were harvesting crops! This fact proves that the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth years of Herod were not sabbath years.

No information is provided by Josephus for Herod’s sixteenth year that would indicate whether or not it was a sabbath. Nevertheless, this fact is in itself noteworthy since there is nothing that stands against this possibility and according to system “A,” Herod’s sixteenth year was a sabbath. Yet Josephus does give us evidence for Herod’s seventeenth year. Josephus writes that “after Herod had completed the seventeenth year of his reign, Caesar came to Syria.”3 Josephus follows this statement with a discussion of Caesar’s visit with Herod, i.e. in Herod’s early eighteenth year.

Tax collection was normally carried out in the seventh month of the year, Tishri, when the harvest was gathered in and people could afford to pay their taxes. But the crops for that period were planted in the last half of the previous year (i.e. beginning in December). The report given by Josephus demonstrates that crops had been planted but that once again there had been a bad harvest. This data shows that the Jews were sowing crops in the seventeenth year of Herod, proving that “Year 17” was not a sabbath year.

“# 14 & 15 Sabbatical Year 22, 15, 8 BC”

King Herod The Great Schmita Coins 22, 15, 8 B.C.

The most abundant coinage of Herod’s reign, likely numbering in the hundreds of thousands, was the light prutah bearing an anchor and double cornucopia with caduceus carries forward the motifs common on the Hasmonean coins and, though undated are likely candidates for Shmitta year coinage during the last 20 years of his reign. Since other sabbatical years produced prutot with different motifs, this prutah likely is associated with the three latest Sabbatical Years, including the years 22, 15 or 8 BCE. This is especially since on these later issues the anchor was prevalent during which time Herod was either planning or building his prize harbor at Caesarea (21-10 BCE).

“# 16 Sabbatical Year 28 CE”

A Sabbatical year in 28 CE. Luke 4:16-20 This was the Sabbatical year and not the Jubilee year as some think.

Luke 4: 16-20 And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up. And as was his custom, he went to the synagogue on the Sabbath day, and he stood up to read. And the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written,

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

And he rolled up the scroll and gave it back to the attendant and sat down. And the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him.

“# 17 Sabbatical Year 42 CE”

A Sabbatical year in 42 C.E. Josephus Antiquities 18

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj22Chap.pdf

King Herod Agrippa I Shmita Coins 42 C.E.

Herod Agrippa, also known as Herod or Agrippa I (11 BC – 44 AD), was a King of Judea from 41 to 44 CE.

Herod Agrippa I minted coins during several years during the years of his reign at the Paneas mint (year 2), the Tiberias mint (year 5) and at Caesarea (year 7 and year eight) all of which were minted with non-Jewish symbols (including human images of himself and the emperor; pagan images of gods and temples) and not during the sabbatical year. However during the 2nd year of his reign, a sabbatical year, he minted myriads of bronze prutot with the parasol and ears of grain, non-offensive symbols to Jews, at the Jerusalem mint.

Herod Agrippa’s non-Jewish ancestry and his Shining Religious Moment during the Sabbatical Year, 42 CE

Mishna Sota 7:8 A. The pericope of the king [M. 7:2a5]-how so?

At the end of the first festival day of the Festival [of Sukkot], on the Eighth Year, [that is] at the end of the Seventh Year, they make him a platform of wood, set in the courtyard.

And he sits on it, as it is said, At the end of every seven years in the set time (Dt. 31:10).

The minister of the assembly takes a scroll of the Torah and hands it to the head of the assembly, and the head of the assembly hands it to the prefect, and the prefect hands it to the high priest, and the high priest hands it to the king, and the king stands and receives it.

But he reads sitting down.

Agrippa the King stood up and received it and read it standing up, and sages praised him on that account. And when he came to the verse, You may not put a foreigner over you, who is not your brother (Dt. 17:15), his tears ran down from his eyes. They said to him, “Do not be afraid, Agrippa, you are our brother, you are our brother, you are our brother!”

He reads from the beginning of “These are the words” (Dt. 1:1) to “Hear O Israel” (Dt. 6:4), “Hear O Israel” (Dt. 6:4), “And it will come to pass, if You hearken” (Dt. 11:13), and “You shall surely tithe” (Dt. 14:22), and “When you have made an end of tithing” (Dt. 26:12-15), and the pericope of the king [Dt. 17:14-20], and the blessings and the curses [Dt. 27:15-26], and he completes the whole pericope. With the same blessings with which the high priest blesses them [M. 7:7f], the king blesses them. But he says the blessing for the festivals instead of the blessing for the forgiveness of sin.

(Mishnah, Neusner English translation)

“# 18 Sabbatical Year 56 CE”

56 C.E. A note of Indebtedness in Nero’s time.

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj23Chap.pdf

“# 19 Sabbatical Year 70 CE”

70 C.E. The Sabbath year of 70/71 C.E.

First Revolt (66–70 CE) Sabbatical Year: 70

During the revolts, when messianic expectation was a key rallying point, the coins used the more unusual term (Geulah instead of Shmitta) for the sabbatical year of Leviticus 25 which specifically deals with the agricultural rules, as opposed to the passage in Deuteronomy 15 which deals solely with the rules of lending, debt and slavery. This term Geulah may also have been used to bolster the messianic expectation of the period. The Messiah as the GOEL/Redeemer would arrive during a Sabbatical year or in a Jubilee year to redeem his people from debt, slavery and oppression and to atone for their sins before God. During other, non-sabbatical, years the term “freedom of Zion/Jerusalem” was used instead. During the first year of the Second Revolt, a sabbatical year, the term Geulah was not limited to the bronze denominations but was added to silver coins as well.

The rabbinical text which deals with issues of chronology, Seder Olam Rabba, states that the year preceding the fall of the Temple (69/70 CE) was a Sabbatical Year. Bronze coins during years two and three of the First Revolt were inscribed Herut tsiyon “the freedom of Zion” which changed with minting of several new bronze issues during year four to Shnat arba lege’ulat tsiyon “Year four of the redemption of Zion”. The term “Redemption” carries more messianic connotations than HERUT/Freedom since the Messiah is to appear as GOEL/Redeemer.

This is recorded in the Soncino translation in Arakin 11b, that the Temple was destroyed “at the end of the seventh [Sabbatical] year”

And we have the following recorded by Qedesh La Yahweh Press. http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj25Chap.pdf

It is unfortunate, indeed, that we possess no direct testimony by any contemporary historian or other such record that can testify directly as to whether or not a sabbath year was in progress during the period that Jerusalem was captured by the Romans (i.e. in the summer of 70 C.E.). Such a document would end all speculation on the issue and would settle the question once and for all.

Nevertheless, Josephus, who was contemporary with that event, goes a long way towards doing just that. In his history of the First Revolt, Josephus mentions an invasion of Judaean Idumaea by Simon ben Gioras in the winter of 68/69 C.E. The fields of Idumaea, we are told, were cultivated. This detail is important because the Idumaeans in this region and of that period were Jewish by religion and would not have cultivated their fields in the few months prior to a sabbath year or during a sabbath year. Therefore, the evidence from Josephus strongly indicates that the sabbath year could not have taken place until the next year (70/71 C.E., Nisan reckoning).

The Chronology of Simon’s Invasion

The sequence of events for Simon’s invasion of Idumaea are as follows: Vespasian, the Roman general, was in Caesarea preparing to march against Jerusalem when word arrived of the death of Emperor Nero.1 Nero died on or about June 9, 68 C.E. Since it was early summer, it would have taken approximately three weeks for news to arrive from Rome to Palestine (this being a reasonable estimate due to the urgency of the message of the emperor’s death).

Vespasian must have heard of Nero’s death on or about the beginning of July, which is supported by comparing the statements of Theophilus and Dio.2 Vespasian, after hearing of Nero’s death and the civil war that ensued, deferred his expedition against Jerusalem, “anxiously waiting to see upon whom the empire would devolve after Nero’s death; nor when he subsequently heard that Galba was emperor would he undertake anything, until he had received further instructions from him concerning the war.”3

In response, Vespasian sent his son Titus to the new emperor for instructions. Yet before Titus could arrive in Rome, while he was still sailing in vessels of war around Achaea, it being “the winter” season, Galba was assassinated” and Otho succeeded to the crown.4

1 Jos., Wars, 4:9:2.

2 Theophilus, 3:27; Dio, 65:1, 66:17; also see above Chap. XXIII, pp. 293f.

3 Jos., Wars,

4:9:2. 4 Ibid.

Titus then sailed back from Greece to Syria and hastened to rejoin his father at Caesarea. “The two (Vespasian and Titus), being in suspense on these momentous matters, when the Roman empire itself was reeling, neglected the invasion of Judaea, regarding an attack on a foreign country as unseasonable, while in such anxiety concerning their own.”5

Otho had ascended to the throne on January 15, 69 C.E. It would have taken about 14 to 21 days for news of Galba’s death to reach Greece where Titus was. Therefore, Titus must have started back for Syria in mid-February and rejoined his father at Caesarea in late February or early March of 69 C.E.

“But another war WAS NOW IMPENDING over Jerusalem.”6 At this point Josephus backs up a little to tell the story of how the Jewish factional leader Simon ben Gioras came to lay siege against Jerusalem. The context of his discussion is that the siege of Simon ben Gioras against Jerusalem was about to occur at the same time that Titus made his return trip from Greece.

In the months before the siege Simon had collected a strong force and had overrun not only the province of Acrabetene but the whole district extending to the border of Idumaea. He then fortified himself in a city called Nain where “he laid up his spoils of corn” and “where most of his troops were quartered.” Here he began training his men “for an attack upon Jerusalem.”7

The Jewish Zealots, who were allied with and had many members from the Idumaeans, fearing an attack by Simon, made an expedition against him (unthinkable in a sabbath year), but they lost the contest. In turn, Simon “resolved first to subdue Idumaea” and forthwith marched to the borders of that country. A battle was fought but no one was the victor. Each side returned home.8 “Not long after,” Simon invaded that country again with a larger force. This time he took control of the fortress at Herodion (Herodium). Through a bit of trickery, Simon was able to convince the Idumaeans that he possessed a force far too great for them to thwart. The Idumaeans unexpectedly broke ranks and fled.9

Simon, thus, “marched into Idumaea without bloodshed,” captured Hebron, “where he gained abundant booty and laid hands on vast supplies of corn,” and then “pursued his march through the whole of Idumaea.”10 On his march through Idumaea, Simon made “havoc also of the country, since provisions proved insufficient for such a multitude; for, exclusive of his troops, he had 40,000 followers.” His cruelty and animosity against the nation “contributed to complete the devastation of Idumaea.”11

Just as a forest in the wake of locusts may be seen stripped quite bare, so in the rear of Simon’s army nothing remained but a desert. Some places they burnt, others they razed to the ground; ALL VEGETATION throughout the country vanished, either trodden under foot or consumed; while the tramp of their march rendered ????? (CULTIVATED LAND) harder than the barren soil. In short, nothing touched by their ravages left any sign of its having ever existed. (Jos., Wars, 4:9:7)

5 Ibid.

6 Jos., Wars, 4:9:3.

7 Jos., Wars, 4:9:3–4, cf. 2:22:2.

8 Jos., Wars, 4:9:5.

9 Jos., Wars, 4:9:5–6.

10 Jos., Wars, 4:9:7.

11 Ibid.

The land was ????? (energon), i.e. “cultivated,” “productive,” “active.”12 This evidence proves that the land in Idumaea was at the time planted with crops. It also places Simon’s invasion in the months after Khisleu (Nov./ Dec.), when the fields are first sown. The Jews under Simon were also harvesting all consumable vegetation, something not done during a sabbath year.

In turn the Zealots captured Simon’s wife and triumphantly entered the city of Jerusalem as if Simon himself had been captured. In response Simon laid siege to Jerusalem (which he would not have done in a sabbath year), causing a great terror among the people there. Out of fear the citizens allowed Simon to recover his wife,13 but he was not yet able to take the city.

Josephus then backtracks to report the events occurring in Rome at that time. Galba was murdered (Jan., 69 C.E.), Otho succeeded to power, and Vitellius was elected emperor by his soldiers. The contest between Otho and Vitellius ensued, after which Otho died, having ruled 3 months and 2 days.14 Otho’s death took place in April of 69 C.E.15

This evidence demonstrates, since agressive war was committed and crops were in production during the winter of 68/69 C.E., that system “B,” which would have the sabbath year begin in Tishri of 68 C.E., is eliminated as a possibility. Also, since the Jews by custom did not plant crops during the six months prior to the beginning of a sabbath year, system “D,” which would begin a sabbath year in the spring of 69 C.E., must also be dismissed.

The Edomite Jews

Those who hold to systems “B” and “D” object to our conclusion. They cannot deny the clear statements of Josephus. Instead, they argue, as Solomon Zeitlin does, that “the laws of the sabbatical year affected only the lands of Palestine, and had no application in Edom or in any other country that was annexed to Palestine.”16 Though this interpretation may at first seem reasonable, the attempt by the advocates of systems “B” and “D” to circumvent the words of Josephus about the events during the winter of 68/69 C.E. cannot bear up against close scrutiny.

First, one must not confuse the original country of Edom (Greek “Idumaea”) with the country of Idumaea of the first century C.E. The Edomites had originally settled in the Khorite country of Seir, located southeast of the Dead Sea.17 The people of Edom are descendants of Esau, who was later called Edom (Red) because he sold his birthright to his brother, Jacob Israel,

12 GEL, p. 261; SEC, Gk. #1753–1756.

13 Jos., Wars, 4:9:8.

14 Jos., Wars, 4:9:9.

15 Tacitus, Hist., 2:47–55.

16 JQR, 9, pp. 90, 101.

17 Deut., 2:5, 12, 22; Jos., Antiq., 1:20:3, 2:1:1; Yashar, 28:20, 29:12–13, 36:15–37, 47:1, 30–32, 56:46f, 57:4–38, 84:5; cf. Gen., 36:20

for a bowl of red soup.18 Before the death of Isaak, the father of both Israel and Edom, Edom migrated and settled in the Kanaani land of Seir the Khorite, located in the mountains southeast of the Dead Sea. Edom made this settlement permanent after Isaak’s death. Later, the Edomite nation killed off the Seiri and became the dominant tribe in that land.19

In the days of Moses the country bordering south of Edom was Qadesh Barnea,20 properly identified by Josephus,21 Jerome, and Eusebius with the district near Petra.22 On Edom’s north side lay Moab,23 their borders touching at the Zered river: the modern Wadi el-Hasa.24 Through Edom’s territory ran the famous King’s Highway, the main highway that today extends from the Gulf of Aqabah to Al Karak.25 The ancient capital city of Edom was Bozrah.26 It was located about 30 miles southeast of the Dead Sea in the mountains east of the Arabah (the long valley located south of the Dead Sea and on the west side of the Seir mountains).27

At the time the Israelites divided up their shares of the Promised Land, Judah’s portion included the Arabah. Judah’s lot also retained Qadesh Barnea, which bordered on the south of Edom and extended southward towards the Gulf of Aqabah (Red Sea).28 Importantly, the Israelites were not permitted to take any part of the land of Edom in their conquest.29 After the Exodus, when the Israelites left the southern border of Edom in an effort to encompass that land so that they might gain access to the King’s Highway without having to pass through Edom’s territory, they went by way of the Arabah south of the Dead Sea.30

On their way north from the Gulf of Aqabah, the Israelites stopped off at Punon,31 identified with modern Feinan, an Edomite border district on Edom’s western side, located on the east side of the Arabah about 25 miles south of the Dead Sea.32 This evidence proves that the original country of Edom proper laid north of Petra, east of the Arabah, and south of the Zered river (Wadi el-Hasa).

The Edomite families remaining in their original homeland were, by the beginning of the reign of King Darius of Persia (521 B.C.E.), driven out of their country by the Nabataean Arabs. These exiled Edomites, in turn, resettled in southern Palestine (cf. 1 Esdras, 4:45–50). The historian Strabo writes:

The Idumaeans (Edomites) are Nabataeans, but owing to sedition they were banished from there, (and) joined the Judaeans. (Strabo, 16:1:34)

18 Gen., 25:19–34, 36:1–43.

19 Gen., 32:3; Num., 24:18; Deut., 2:12, 22; Yashar, 47:1, 57:13–38.

20 Num., 20:16.

21 Jos., Antiq., 4:4:7.

22 Onomastica, pp. 108, 233.

23 Deut., 2:1–5, 8–18; cf. Num., 21:10–12; Judg., 11:16–18.

24 DB, p. 763; NBD, p. 1359; WHAB, p. 39a.

25 Num., 20:14–21; cf. 21:21f; also see MBA, maps 9, 10, 52, 104, 126, 208; WHAB, p. 41, 65b; NBD, p. 700.

26 Gen., 36:33; Isa., 34:6, 63:1; Jer., 49:13, 22; Amos, 1:12; Mic., 2:12.

27 NBD, p. 165; MBA, maps 52, 104, 155.

28 Josh., 10:16, 15:1–3, 18:18; Num., 34:3–4.

29 Deut., 2:4–5.

30 Deut., 2:8; cf. Num. 21:21ff; Yashar, 85:14.

31 Num., 21:4–11; cf. 33:42ff.

32 Onomastica, pp. 123, 299; MBA, p. 182, map. 52; ATB, p. 160.

The Nabataeans were an Arab tribe named after Nebaioth, the son of Ishmael, the brother-in-law of Edom.33 In the post-exile period this tribe came to dominate the ancient Edomite country on the southeast side of the Dead Sea. They made their capital the ancient city of Petra.34

The Edomi were not Nabataeans; but, after they and their original homeland came to be dominated by the Nabataeans in the late Babylonian period, the Greeks identified these Edomi with the latter. Strabo, accordingly, identified the Idumaeans with their kinsmen tribe because they had once dwelt with the Nabataeans in part of the land presently known to him as Nabataea.

The territory occupied by the Edomites in the first century C.E., on the other hand, was located in the southern half of Judaea and was part of the Holy Land. Josephus states that the land of Idumaea that existed from the second century B.C.E. until the first century C.E. laid in “the latitude of Gaza” and was “conterminous with” the territory then held by the Jews.35 Its cities included Hebron (formally an important Jewish city in the inheritance of Judah);36 Adora (located 5 miles southwest of Hebron); Rhesa (8 miles south of Hebron); Marisa (1 mile south of Bit Jibrin); Thekoue (5 miles south of Bethlehem); Herodion (3 miles northeast of Thekoue); and Alurus (4 miles north of Hebron).37

Josephus makes Idumaea one of the 11 districts of Judaea.38 In his book on the Jewish Wars, Josephus reports the defection “in many parts of Idumaea, where Machaeras was rebuilding the walls of the fortress called Gittha.”39 In another version of this story, Josephus states it was “a good part of Judaea” that revolted when Machaeras fortified the place called Gittha.40 Therefore, the first century C.E. country of Idumaea is interchangeably used as part of Judaea.

In pointing out how the Holy Land was divided up amongst the 12 tribes of Israel in the days of Joshua the son of Nun (1394 B.C.E.), Josephus uses the place names of cities and regions in his own day (the first century C.E.). In the allotments that came to the Israelite tribes of Judah and Simeon (Simeon obtaining a share of Judah’s territory),41 Josephus gives the following description:

When, then, he had cast lots, that of Judah obtained for its lot the WHOLE OF UPPER IDUMAEA, extending (in length) to Jerusalem and in breadth reaching over to the lake of Sodom (Dead Sea); within this allotment were the cities of Ashkelon and Gaza. That of Simeon, being the second, obtained the portion OF IDUMAEA bordering on Egypt and Arabia. (Jos., Antiq., 5:1:22) —

33 Gen., 25:13, 28:9; Jos., Antiq., 1:12:4.

34 Strabo, 16:4:21.

35 Jos., Apion., 2:9.

36 E.g. see Josh., 21:9–11, 11:21, 15:1–14, 14:6–15.

37 Jos., Wars, 1:2:6, 1:13:8, 4:9:4–7, Antiq., 13:9:1, 14:13:9; and so forth.

38 Jos., Wars, 3:3:5.

39 Jos., Wars, 1:17:2.

40 Jos., Antiq., 14:15:11.

41 For the location of the inheritance of Judah and Simeon see Josh., 15:1–63, 19:1–9. The tribe of Simeon took its portion out of the land allotted to Judah, see Josh., 19:1.

Diodorus states that the Dead Sea extends along the middle of the satrapy of Idumaea42 (i.e. the Dead Sea laid on the eastern side of Idumaea). Pliny points out that “Idumaea and Judaea” were part of the “seacoast of Syria,”43 i.e. they both border upon the Mediterranean Sea. He adds that Palestine begins with the region of Idumaea “at the point where the Serbonian Lake comes into view.”44 The Serbonian Lake is located along the Mediterranean Sea, forming the northeastern sector of the Sinai Peninsula. Pliny also makes Judaea proper lie between Idumaea and Samaria.45

Strabo notes, “As for Judaea, its western extremities towards Casius are occupied by the Idumaeans and by the lake (Serbonia).”46 The famous second century C.E. geographer Ptolemy makes Idumaea one of the districts of greater “Palestina or Judaea.” He writes that “all” of Idumaea lies “west of the Jordan river.” Ptolemy describes and defines Idumaea and its cities as that district lying immediately south of Judaea proper.47

This geographical data proves beyond any doubt that the country of Idumaea which existed in the first century C.E. occupied a portion of the Promised Land that had formally been given by allotment to the Israelite tribes of Judah and Simeon. The land they possessed, therefore, was part of the Holy Land; more specifically, part of greater Judah (Simeon’s portion being extracted out of Judah’s share). It stands to reason that if part of the Holy Land is occupied by those professing the Jewish faith, in the eyes of the Jews, it certainly would be subject to the Laws of Moses.

What then of the Idumaean religious beliefs? In the reign of John Hyrcanus (134/133–105/104 B.C.E.), the Jews conquered the country of Idumaea.48

Hyrcanus also captured the Idumaean cities of Adora and Marisa, and after subduing all the Idumaeans, PERMITTED THEM TO REMAIN in the country SO LONG AS they had themselves circumcised and WERE WILLING TO OBSERVE THE LAWS OF THE JEWS. And so, out of attachment to the land of their fathers, they submitted to circumcision and to making their manner of life conform in all other respects to that of the Jews. AND FROM THAT TIME ON THEY HAVE CONTINUED TO BE JEWS. (Jos., Antiq., 13:9:1)

No other neighboring countries located outside of the lands anciently inhabited by the Israelites and conquered by the Jews in the second and first centuries B.C.E. were forced to meet the requirements of either becoming Jewish by religion and practice or suffer under the threat of being forced to vacate their land. Nevertheless, there are two extremely important questions that have not been asked in reference to this above cited passage: “Is this exemption true for those

42 Diodorus, 19:98.

43 Pliny, 5:13.

44 Pliny, 5:14.

45 Pliny, 5:15.

46 Strabo, 16:2:34.

47 Ptolemy, 5:15, and Map of Asia Four.

48 Jos., Antiq., 13:9:1, Wars, 1:2:6.

people living on territories anciently inhabited by the Israelites?” and, “Why would the Jews demand compliance from these Idumaeans?

The answers are easily unveiled. When the Jews dominated Samaria and the Trans-Jordan districts, once inhabited by the House of Israel, Jewish customs were also demanded. The Samaritans, for instance, had long practiced a form of Judaism and, for the Jews, were not an issue.49 But the Ituraean Arabs give us an excellent example. A tribe of Ituraeans lived in a Trans-Jordan district once inhabited by the Israelite tribe of Manasseh. When a portion of them were conquered by the Jewish king Aristobulus (104/103 B.C.E.), and their territory annexed, they were joined to the Jews “by the bond of circumcision.”50

The Idumaeans, meanwhile, were living in that part of the Holy Land which historically belonged to the Jews, who had occupied it centuries before the Jewish exile to Babylonia during the sixth century B.C.E. The Jews identified themselves with their own heritage in Judah yet they still saw reasons to require the conversion of the foreign nations now occupying the territory that had once belonged to the House of Israel. This requirement was even more stringent within territory traditionally considered Judahite. In the Torah, aliens dwelling with the Israelites were required to observe the sabbath year.51 As a result, either the Edomites, who were living in Judah proper and not just greater Israelite territory, had to conform to Jewish law or they had to leave. The Idumaeans chose to stay in the land, “And from that time on they have continued to be Jews!”

In the days of King Herod the Great of Judaea an Idumaean named Costobarus was appointed governor of Idumaea and Gaza. Costobarus held the belief that the Idumaeans should not have adopted the customs of the Jews, so he sent to Cleopatra of Egypt in an attempt to have Idumaea stripped from Judaea as a possession. The attempt failed, but in discussing this issue Josephus also comments that in earlier times the Jewish priest “Hyrcanus had altered their (the Idumaeans’) way of life and made them adopt THE CUSTOMS AND LAWS OF THE JEWS.”52 Strabo writes:

The Idumaeans are Nabataeans, but owing to a sedition they were banished from there, joined the Judaeans, and SHARED IN THE SAME CUSTOMS WITH THEM.53

Antipater, the father of the Judaean king Herod (37–4 B.C.E.), was an Idumaean held in high esteem among the Idumaean people.54 Though Herod’s father was Edomite, the Jews themselves proclaimed that he “was a Jew.”55 Four of Herod’s wives (Doris, Mariamme the daughter of Alexander, Mariamme the daughter of Simon, and Cleopatra) are know to be Jewish.56 In fact, Mariamme the daughter of Alexander was the granddaughter of the Jewish

49 Cf. 2 Kings, 17:24–28; Jos., Antiq., 9:14:1–3.

50 Jos., Antiq., 13:11:3.

51 E.g. Lev., 25:2–7.

52 Jos., Antiq., 15:7:9.

53 Strabo 16:2:34

54 Jos., Wars, 1:6:2, 1:13:7, 2:4:1, Antiq., 14:1:3, 14:7:3, 14:15:2.

55 Jos., Wars, 2:13:7.

56 Doris was of Herod’s “own nation,” i.e. an Edomite (Jos., Antiq., 14:12:1), yet is said to be “a native of Jerusalem” (Jos., Wars, 1:22:1) and “a Jewess of some standing” (Jos., Wars, 12:3). Mariamme, the daughter of Alexander, the son of Aristobulus, was the granddaughter of the high priest Hyrcanus (Jos., Wars, 1:12:3, 1:17:8, Antiq., 14:12:1, 14:15:14). The second Mariamme was the “daughter of Simon the high priest” (Jos., Antiq., 15:9:3, 18:5:4). Cleopatra is also called “a native of Jerusalem.” On the ten wives of Herod the Great see Jos., Antiq., 17:1:1–3; Wars, 1:24:2, 1:28:4; HJP, 1, pp. 320f.

high priest named Hyrcanus and the other Mariamme was the daughter of the high priest named Simon.57

It would not have been possible for Herod to have retained the Judaean crown if he had not himself been Jewish by religion. Therefore, the king of Judaea, at the time that the messiah was born, though Edomite by descent was Jewish by religion. This fact symbolizes the general merger of the Judahites and Edomites of Idumaea during this and subsequent periods. Though up until the first century C.E. the Judahites and Edomites could distinguish between themselves, foreigners classed them all as Jews. In time even their own ability to distinguish one from the other had passed away.

In religious matters the Idumaeans were generally in alliance with the Zealots, one of the strictest religious sects in ancient Judaism.58 The Idumaean Jews attended the major religious feasts at Jerusalem and were also a bulwark in the First Revolt against the Romans (66–70 C.E.).59

Conclusion

There can be no doubt. The Idumaeans of the first century C.E. were not only Jews by religion but were living in the Holy Land—and not in just any part of the Holy Land but in that portion which had historically belonged to the tribe of Judah. Under Jewish domination they were required to adhere to the Jewish faith or else be forced to abandon the country. At the same time, the Idumaeans were in close alliance with the Zealots, a strict Jewish sect, and demonstrated their loyalty to their faith in the Jewish war against Rome.

With these details we are compelled to the conclusion that the Edomites living in southern Judaea were strict adherents to Jewish law. If they had not been, an alliance with the Zealots would have been impossible and the other Jews would have found grounds to expel them from the country.

These facts force us to conclude that when Simon invaded the country of Idumaea in the winter of 68/69 C.E.—an act itself not committed in a sabbath year—there was no possible way that these Idumaean Jews would have avoided the sabbath year laws. But since they did cultivate their fields, we are presented with clear evidence that the winter of 68/69 B.C.E. was not part of a sabbath year. Further, since the crops of this planting season would normally be harvested after the beginning of the next year (69/70 C.E., Nisan reckoning), we have evidence that this next year was also not a sabbath.

The attack on Jerusalem by the Jewish factional leader Simon ben Gioras and the crops grown in Idumaea during the winter of 68/69 C.E. eliminates the cycles of both systems “B” and “D” from consideration (see Chart A). System “C” retains the problem of beginning with a Tishri year. Therefore, by default, the sabbath year cycle once again conforms to system “A.” We are left with the conclusion that 70/71 C.E., Nisan reckoning, the year that Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans, was a sabbath year (see Charts A & B).

57 Ibid.

58 E.g. Jos., Antiq., 4:4:1–4:5:2.

59 E.g. Jos., Antiq., 17:10:2, Wars, 2:3:2, 5:6:1, 6:8:2.

SUmmerizing all of this once again.

We have no documents that outright prove that 70 CE was the Sabbatical year. The same year as the destruction of the Temple.

BUT……

Josephus records a history of events that will prove that the year the temple was destroyed was a Sabbatical year and that it was 70 C.E.

In the winter of 68-69 CE. Simon ben Giora invaded Judaean Idumaea

The fields were at this time cultivated.

March of 69 CE. Simon ben Giora fortified himself in Nain and stocked up the crops of corn. Jewish Zealots attacked him in Nain. Something you did not do in a Sabbatical year.

Notice he stocked up crops in the year. You do not harvest and stock up crops if it is the Sabbatical year. And they would never have attacked in the Sabbatical year. It was forbidden. These are zealots.

Late Summer of 69 CE. Simon ben Gioras took Hebron and all of Idumaea and all the crops

All the land was cultivated and with crops. It was 69 C.E.

They were at war

It was not a Sabbatical year 68-69

We can also date the events of Titus with Roman history and know the year He attacked Jerusalem was 70 C.E.

Prior to becoming Emperor, Titus gained renown as a military commander, serving under his father in Judaea during the First Jewish-Roman War. The campaign came to a brief halt with the death of emperor Nero in 68, launching Vespasian’s bid for the imperial power during the Year of the Four Emperors. When Vespasian was declared Emperor on 1 July 69, Titus was left in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion. In 70, he besieged and captured Jerusalem, and destroyed the city and the Second Temple. For this achievement Titus was awarded a triumph: the Arch of Titus commemorates his victory to this day.

The Year of the Four Emperors was a year in the history of the Roman Empire, AD 69, in which four emperors ruled in succession:

The suicide of emperor Nero, in 68, was followed by a brief period of civil war. Between June of 68 and December of 69, Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of Galba, Otho and Vitellius until the final accession of Vespasian,

The Senate acknowledged Vespasian as emperor on the day after Vitellius was killed. It was December 21, 69, the year that had begun with Galba on the throne.

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called The Great Revolt (Hebrew: ???? ??????, ha-Mered Ha-Gadol, Latin: Primum populi Romani bellum in Iudaeos[citation needed]), was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews of Judea Province (Iudaea) against the Roman Empire. The second was the Kitos War in 115–117, which took place mainly in the diaspora, and the third was Bar Kokhba’s revolt of 132–135 CE.

The Great Revolt began in the year 66 CE, originating in the Roman and Jewish religious tensions. The crisis escalated due to anti-taxation protests and attacks upon Roman citizens.[3] The Romans responded by plundering the Jewish Temple and executing up to 6,000 Jews in Jerusalem, prompting a full-scale rebellion. The Roman military garrison of Judaea was quickly overrun by rebels, while the pro-Roman king Agrippa II, together with Roman officials, fled Jerusalem. As it became clear the rebellion was getting out of control, Cestius Gallus, the legate of Syria, brought in the Syrian army, based on Legion XII Fulminata and reinforced by auxiliary troops, to restore order and quell the revolt. Despite initial advances and conquest of Jaffa, the Syrian Legion was ambushed and defeated by Jewish rebels at the Battle of Beth Horton with 6,000 Romans massacred and the Legion’s Aquila lost – a result that shocked the Roman leadership.

Later, in Jerusalem, an attempt by Menahem ben Yehuda, leader of the Sicarii, to take control of the city failed. He was executed and the remaining Sicarii were ejected from the city. A charismatic, but radical peasant leader Simon bar Giora was also expelled by the new Judean government, and Ananus ben Ananus began reinforcing the city. Yosef ben Matityahu was appointed the rebel commander in the Galilee and Elazar ben Hananiya as the commander in Edom.

The experienced and unassuming general Vespasian was given the task of crushing the rebellion in Judaea province. His son Titus was appointed as second-in-command. Given four legions and assisted by forces of King Agrippa II, Vespasian invaded Galilee in 67. Avoiding a direct attack on the reinforced city of Jerusalem, which was defended by the main rebel force, the Romans launched a persistent campaign to eradicate rebel strongholds and punish the population. Within several months Vespasian and Titus took over the major Jewish strongholds of Galilee and finally overran Jodapatha, which was under the command of Yosef ben Matitiyahu, after a 47-day siege. Driven from Galilee, Zealot rebels and thousands of refugees arrived in Judea, creating political turmoil in Jerusalem. A confrontation between the mainly Sadducee Jerusalemites and the mainly Zealot factions of the Northern Revolt under the command of John of Giscala and Eleazar ben Simon, erupted into bloody violence. With Edomites entering the city and fighting by the side of the Zealots, Ananus ben Ananus was killed and his faction suffered severe casualties. Simon Bar Giora, commanding 15,000 troops, was then invited into Jerusalem by the Sadducee leaders to stand against the Zealots, and quickly took control over much of the city. Bitter infighting between factions of Bar-Giora, John and Eleazar followed through the year 69.

After a lull in the military operations, owing to civil war and political turmoil in Rome, Vespasian was called to Rome and appointed as Emperor December 21, 69. With Vespasian’s departure, Titus moved to besiege the center of rebel resistance in Jerusalem in early 70. The first two walls of Jerusalem were breached within three weeks, but a stubborn rebel standoff prevented the Roman Army from breaking the third and thickest wall. Following a brutal seven-month siege, during which Zealot infighting resulted in the burning of the entire food supplies of the city, the Romans finally succeeded in breaching the defences of the weakened Jewish forces in the summer of 70. Following the fall of Jerusalem, Titus left for Rome, leaving Legion X Fretensis to defeat the remaining Jewish strongholds, finalizing the Roman campaign in Masada in 73–74.

We have crops in the field of 69. We have Vespasian leaving to be Emperor in Dec of 69. Leaving Titus to finish job.

Josephus would then become the historical writer for Vespasian.

Vespasian left Judea and was crowned Emperor December 21 69 C.E.

Titus turns to Jerusalem and breaches the first two walls before having a 7-month siege on the 3rd wall. It is now 70 C.E. and the Temple and the city finally fell on Tish B’av. in August 70 CE. The 9th of Av which is the 5th month. Meaning the first sieges began in the 11th month of the year 69 January of February.

“# 20 Sabbatical Year 133 CE Rental Contracts & Coins”

133 C.E. Rental contracts before Bar Koch bah Revolt

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj26Chap.pdf

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj28Chap.pdf

Exclusively during year one of the second revolt is leGeulat Yis(rael) “For the redemption of Is(rael)” inscribed upon both silver and bronze coins. During year two, the coins proceed to make exclusive use of the phrase SH B leHerut Yisrael “year 2 of the liberation of Israel” on silver issues and on all but one rare bronze issue (which maintained the phrase from the first year). During years three and four of the revolt issues are undated and change to read leHerut Yerushalem “for the freedom of Jerusalem”.

“# 21 Sabbatical Year 140 CE Rental Contracts”

140 C.E. Rental contracts before Bar Koch bah Revolt

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj26Chap.pdf

http://www.yahweh.org/publications/sjc/sj28Chap.pdf

“# 22 Tombstone # 1 – 360 CE Naveh #18”

Tombstones written in the Aramaic and Hebrew inscriptions are very rare to find and we have 12 of them discovered to date. I have read there are about 30 known.

Tombstone #1-360 CE Naveh #18 “This is the grave of Mousis (Moshe) son of Marsa who died in year three of the Sabbatical cycle, in the month of Kislev, on the twenty-seventh day of it, which is the year 290 after the destruction of the Temple.” 290 + 70 = 360

JOURNAL ARTICLE

A Bilingual Tombstone from Zo’ar (Arabia) (Hecht Museum, Haifa, Inv. No. H-3029, Naveh’s List No. 18)

Hannah M. Cotton and Jonathan J. Price

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

Bd. 134 (2001), pp. 277-283

Published by: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20190821

http://mushecht.haifa.ac.il/hecht/abstract/15e/Abstracts.pdf

“# 23 Tombstone # 2 – 393 CE Naveh’s # 17”

Tombstone #2-393 CE Naveh’s # 17

The oldest stone from Tzo’ar has a double dating which has been published now: stone ?/7 from the year 323 to the destruction which is the first year to the Shemitah.

323 + 70 = 393 CE and it is the first year of the Shemitah cycle. I have no other information on it other than this mention by Joseph Naveh.

More on the Tombstones of Zoar Joseph Naveh 1999 http://www.jstor.org/stable/23601219?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Translation into English by Yoel Halevi

I will include the translated paper here for your viewing. But I got the above information from the very last line as if in passing.

More on the Tombstones of Tzo’ar

Yoeseph Naveh/ Tarbitz 1999, pp.581-586

With the publication of Issachar Stern of four more stones from Tzo’ar, the number of stones published so far is 16. Recently I received a photograph of another stone in the antiques market. This is the transcription of stone 17:

May the spirit of ‘amran son of Yodan rest

who died on the month of Nissan (1st month), on the tenth

day of the month

on the sixth year

of the Sehmitah, which is

year four hundred

thirty-three

to the destruction of the temple

Peace on Israel

It seems we have reached the point where there is a need for a mid-way summery, and to analyze the style of the 17 stones, and to examine the script, language and spelling of the writers.

(from page 582-584 the writer expands on writers and their skills. The main point is that there were different levels of writers, and that the lower level ones made mistakes. I don’t think there is a need to translate all of the sections due to the fact that most of it is linguistic issues which will not be understood by someone who doesn’t have a background in Hebrew and Aramaic. I am only going to present some of the points so you have an idea of what he is talking about)

Stones written by experts

Stone To the destruction To the Shemitah Month ?? 14 398 5 Elul ?? 11 398 6 Kislev ?? 17 433 6 Nissan ? 3 435 7 Elul

Main points:

- The stones were written by expert in a consistent format (even though they were written 35 years apart).

- Spelling is sometimes vulgar by adding ? to mark the long vowel â

- Omission of consonants at the end of lines due to the lack of space

- Some readings are problematic (such as identifying names) due to the stones being broken

- Some spelling mistakes are found, repetition of words

- Issues of loaning words from other languages, or using Aramaic words in a different meaning than Aramaic. Use of words in the Syriac

From page 584

The stone in question (??/14) was written by an expert, and there is no reason to believe that this write would write ??? ?????- fifth day, but rather ??? ???? ???- “fifth day of the t(enth)”, meaning after the word he intended to write “tenth”; however, because he did not have space to finish the word, he erased or abandoned the two last consonants at the end of the line, and started to write again on the third line the word “twenty”. This phenomenon is known to us from stone ??/11 where the scribe wrote the name “Ester” between the lines.

Stone ??/13 is beautifully engraved and has no count of years to the Shemitah. The deceased is probably “the mother of Jesus”. It is correct that the writing of the second consonant is long (?/?) and the word might be Umah and not Imma. We might be looking at an Arabic version of the word “Mother”

(the writer continues to discuss issue of spelling and writing. Again, the main issue to realize is that there are different levels of writing in the stones. The different levels are important because they reflect on how proficient the writers were in presenting the information. Any mistakes made in the inscriptions affects our understanding of the dating system in the stones).

Stern is correct when he says “the researchers of the stones need to be careful…from concluding any absolute/final conclusion from the details in the stones”. As we have seen in three of the stones, there are mistakes in stones 1, 15 and 16. These mistakes are in both language and dating. However, Stern also sees mistakes in the dating in the three stones which were written in Elul (3, 10 and 14). Stones 3 and 14, which were probably written by expert hands were discussed above. Logic dictates that they did not make mistakes in the dating. It also seems that stone 10, even though it was written by a non-expert in writing, was accurate in the dating of the years. Maybe it is necessary to consider the dating of the destruction from the 9th of Av seriously?

Appendix

The Ruben and Edith Hecht museum in Haifa had purchased a bi-lingual stone (Greek and Aramaic). Part of the Greek is difficult to decipher. The full stone was published by Prof.Hanna Koten and Nave:

On the third year of the Shemitah, on the month of Kislev on the twenty seventh day, which is the year 290 to the destruction of the temple

This is the oldest stone with a double dating. Older than this stone is stone ?/6 from the year 282 to the destruction which does not count to the Shemitah. Another stone which does not count to the Shemitah is stone ?13 (year 305 to the destruction). The year ?? (=290) to the destruction, and the year three to the Shemitah in stone ??/18 fit the dates of most of the stones of Tzo’ar. The oldest stone from Tzo’ar has a double dating which has been published now: stone ?/7 from the year 323 to the destruction which is the first year to the Shemitah.

“# 24 Tombstone # 3 – 393 CE Naveh’s # 7”

Tombstones # 3 – 393 CE Naveh’s # 7

This is the tombstone of Jacob Son of Samul, who died on The second day (Monday), forty years old, on the third day of the month of Iyar (2nd month), on the first year of the Shemitah year three hundred and twenty three to the destruction of the temple 323 + 70 = 393 CE

Aramaic Tombstones from Zoar

Which is found at this link and is translated for me by Yoel Halevi.

“# 25 Tombstone # 4 – 416 CE Naveh’s # 2”

Tombstones # 4 – 416 CE Naveh’s # 2 This is the tombstone of Esther the daughter of Adayo, who died in the month of Shebat of the 3rd year of the Sabbatical cycle, the year three hundred 46 years after the destruction of the Temple. Peace. Peace. Upon her. 346 + 70 = 416

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Another Jewish Aramaic Tombstone From Zoar

JOSEPH NAVEH

Hebrew Union College Annual

Vol. 56 (1985), pp. 103-116

Published by: Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23507649

“# 26 Tombstone # 5 – 416 CE Naveh’s # 12”

Tombstones #5 – 416 CE Naveh’s # 12

Appendix- stone ?? (12)